Edward Cormier

Father Edward Cormier

Priest, Archdiocese of Moncton, New Brunswick. Ordained 26 May 1949.

____________________________________

Archbishops of Moncton Archdiocese from time of Father Cormier’s ordination to early 2000s: Norbert Robichaud (25 July 1942 – 23 Mar 1972) ; Donat Chiasson (23 March 1972 – 21 September 1995);Ernest Léger (27 November 1996 – 16 March 2002 ) André Richard, C.S.C. (16 March 2002 – 15 June 2012)

_____________________________________

Unless otherwise indicated the following information is drawn from copies of the annual Canadian Catholic Church Directories (CCCD) which I have on hand, and media (M)

2010: not listed in CCCD index

2002, 2000, 1999, 1991: address is apartment in Moncton, New Brunswick (CCCD)

1985: Pastor, St. Bernadette Roman Catholic Church, Moncton, New Brunswick (CCCD)

1973-73: address in index shows him as assistant at Ss Simon’s and Jude’s Roman Catholic Churches, Tignish, Prince Edward Island (Pastor Father A. Bradley . (CCCD) I wonder if there was an error here? There is another Father Edward Cormier from the Diocese of Charlottetown who was ordained in 1968 whose name is not listed in the ’72-’73 index? Did the Father Cormier from New Brunswick show up in the Diocese of Charlottetown in the early 70s? I don’t think so, but may well be mistaken. If anyone knows with certainty please let me know. )

1971-72: Pastor, St. Anne Roman Catholic Church, Sainte Anne, New Brunswick (CCCD)

1968-69, 1967: Pastor, Immaculate Conception Roman Catholic Church, Acadieville, New Brunswick (CCCD)

1959: Pastor, Pointe Sapin Roman Catholic Church with mission in Claire Fontaine New Brunswick (CCCD)

26 May 1949: ORDAINED (CCCD)

____________________________________________

56 lawsuits against Catholic Church that allege sexual abuse are before N.B. courts

Every month, new legal action is taken against the church in Moncton, Bathurst and Edmundston

Posted: Nov 15, 2017 6:00 AM ATLast Updated: Nov 15, 2017 9:54 AM AT

By Gabrielle Fahmy

A lawyer for victims thinks Leger could have been one of the most prolific child abusers in the Catholic church, making hundreds of victims. (CBC)

Almost every month for a year, lawsuits have been filed against the Catholic Church in New Brunswick by alleged victims seeking compensation for sexual abuse by priests.

Many of the priests are dead, but that hasn’t stopped the lawsuits in Moncton, Bathurst and Edmundston from piling up.

CBC News has found at least 56 lawsuits are still before the courts, despite an extensive conciliation process a few years ago.

At least 11 priests are targeted in the accusations, and one name appears far more often than others.

“It’s very difficult to see all these new allegations coming in,” said Moncton Archbishop Valéry Vienneau.

“We are going through a very difficult time. It certainly has not helped our credibility, as priests and as a church.”

Thirty-two of the accusations are against one individual — Camille Leger.

Leger was the priest in the Sainte-Thérèse-d’Avila Parish in Cap-Pelé between 1957 and 1980. He died in 1990 without ever being accused or convicted of any crimes. His accusers all came forward after his death.

The archbishop said he was surprised by the sheer number.

“It seems that he was a predator all the years that he was in that parish,” Vienneau said.

Moncton, N.B., Archbishop Valéry Vienneau said it has been difficult seeing so many allegations continuing to surface against the church. (CBC)

According to the court documents, most of Leger’s alleged victims were young boys, generally between seven and 15 years old.

Many of them were altar boys at the parish, or boy scouts, who were chaperoned by Leger.

They all allege in court documents that Leger developed a close relationship with them, where he was able to be alone with them.

The sexual abuse often took place in Sainte-Therese-d’Avila church itself, in Leger’s car, during church-organized trips or at boy scout camp, it’s alleged.

For some, the abuse allegedly went on for up to seven years, and Leger is accused of using his position of authority to make sure his victims kept silent.

In 2012, Leger’s name was stripped from the Cap-Pelé arena after allegations of sexual abuse surfaced. (CBC)

Vienneau, also from Cap-Pelé, was 10 years old when Leger started working at Sainte-Therese-d’Avila.

He said he was never a victim of the abuse himself and only found out about the allegations much later.

But he knew many of the alleged victims, and this has been especially difficult for him.

‘A lot of them never told their story to anyone, not even in their family.’ – Michel Bastarache, conciliator

He said they often come to see him.

“It’s not easy to talk about that,” he said. “Even if it’s 40, 50, 60 years ago. It’s not. Some of these victims have never spoken about what happened to them, to anyone.”

Vienneau admitted that lawyers for the archdiocese sometimes advise him against speaking to the victims, but said that as a pastor, he feels that he must.

Number shocks former judge

The 56 new lawsuits were all filed after an extensive conciliation process.

Between 2012 and 2014, retired judge Michel Bastarache, who was brought in by the church, spoke to hundreds of victims and worked out a compensation formula for the church to pay them all.

In the end, the Archdiocese of Moncton had to come up with $10.6 million for victims, and the Diocese of Bathurst $5.5 million.

Victims received between $15,000 and $300,000, depending on the severity of the abuse, how old they were when it started, and how many years it lasted.

Retired judge Michel Bastarache was surprised to see so many lawsuits still active against the Catholic Church in New Brunswick after the conciliation process he led. (CBC)

Bastarache said the conciliation process had to be delayed three times to accommodate new victims, which is why he’s taken aback by so many lawsuits still before the courts.

“I’m just surprised that the numbers are so high,” he said.

He also wonders why these alleged victims didn’t take advantage of the process and are choosing to go to court instead.

“I heard about a hundred victims in Bathurst, another hundred in Moncton, and those people — 90 per cent of them, wanted absolute confidentiality,” said Bastarache.

“A lot of them never told their story to anyone, not even in their family.”

Yvon Arsenault, now serving a four-year prison sentence and awaiting another criminal trial for sexual abuse, is also heavily targeted by current civil suits. (CBC)

Finger pointed at church, too

The Catholic Church is named in all the lawsuits, accused of knowing or saying it should have known about the alleged abuse.

The allegations haven’t been tested in court.

One lawsuit claims the church knew Leger took an unusual interest in children, that some parents had made complaints about him, that he spoke of his “sins” to other priests during confession, and that he was even reported to archdiocese officials for sexual misconduct, yet nothing was done to stop the abuse.

‘It was seen as sin. Today we see it as a sin, but we also see it as a crime.’ – Valéry Vienneau, Moncton archbishop

Fernand Arsenault, a priest for 20 years before he chose to leave the church, knew members of the community and is saddened every time he hears of new allegations of sexual abuse.

He accused the church of turning a blind eye to the abuse and concealing the crimes of those priests.

“It’s a terrible mistake,” said Arsenault. “Because we would have saved many lives.”

Arsenault said that years ago, if a priest reported another priest, he would have been punished, not the abuser.

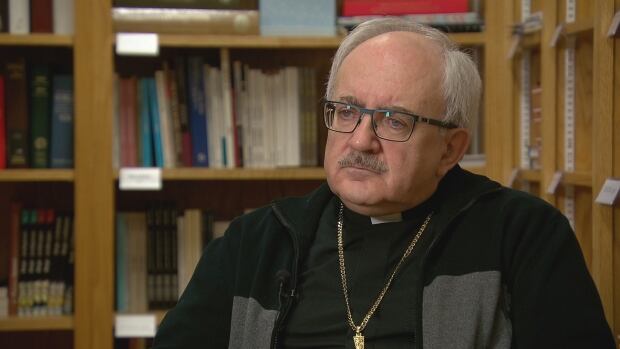

Former priest Fernand Arsenault has accused the church of concealing the crimes of priests who were abusing children. (CBC)

But the church, in every filed statement of defence, has systematically denied knowing about any of the abuse at the time.

The archbishop said it was a different culture back then, and these things weren’t talked about.

“We were in a culture where everything was hidden,” Vienneau said. “Nowadays everything is open.”

“Sometimes we judge those 30, 40 years with the eyes of today,” he said. “That is very difficult too. Because in those days a lot of that was not seen as crime.

“It was seen as sin. Today we see it as a sin, but we also see it as a crime.”